Olufunmilayo Ransome-Kuti was born in 1900 in Abeokuta, Nigeria, to a seamstress and a small planter whose father had been an emancipated, baptized slave returnee from Sierra Leone. She received a Western education up to secondary school, before pursuing further education in England from 1919 to 1923. There she discovered socialism and anti-colonialism.

When Ransome-Kuti returned to Abeokuta, she made a point of speaking Yoruba rather than English, even in her dealings with the colonial authorities. She emphasized the need for unity between ‘elite’ women and the vigorous market women of the town, for whom she organized night schooling through a ‘ladies club’ that she established. In 1944 the club expanded to include the market women and, in 1945, defended them when the government began taking their rice without compensation. Ransome-Kuti’s calls to the press caused the rice controls to be lifted.

As the ladies’ club became more politicized, it was renamed the Abeokuta Women’s Union (AWU) in 1946. Through this union, Ransome-Kuti organized women in Abeokuta to protest against colonial taxation and other unfavourable policies under the slogan ‘No taxation without representation.’ Taxation was a particularly sore issue for the women of Abeokuta: girls were taxed at 15 and boys at 16, and wives were taxed separately from their husbands, irrespective of their income. The women considered the taxes ‘foreign, unfair and excessive.’[1]

The women also protested against the corruption of the traditional rulers, and their failure to defend the women’s demands or to challenge the colonial authorities. One remarkable event organized by the women’s union was the protest against the alake, the king of the town, for enforcing food trade regulations that made life uncomfortable for the people. As with the Igbo women in 1929, the Egba women of Abeokuta focused their opposition on a local representative of British power rather than on British power itself.

Ademola II, Abeokuta’s new alake, and the first to have had a European-style education, came to power in 1920. He took advantage of his position and British support to steal lands and embezzle taxes. As early as 1938, a violent protest took place in front of his palace. Anger mounted again during World War II when the alake took advantage of colonial orders to increase requisitions. Women were his first targets because they brought chickens, yams, gari (cassava meal) and rice into the city. All the alake had to do was set up a few roadblocks in order to confiscate a large part of the women’s wares, offering the justification that no one should eat as long as the soldiers had not been fed. Women, paying both their own taxes and, through their work, some of their husbands’ taxes, were providing at least half the district’s revenues. They became more and more impatient, not only with the ill-treatment they endured to make them pay these taxes, but also with the fact that, despite the obligations imposed on them, they had neither the right to vote nor any representation—merely the right to complain of having been beaten and bullied!

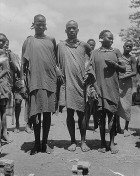

The women’s protest was long and protracted. Ransome-Kuti is said to have led training sessions for their demonstrations, which they referred to as ‘picnics’ or ‘festivals’ as they were unable to get official permits. The campaign against the alake publicly started with a petition, which resulted only in an increase of taxation on women. When thousands of women converged in protest at the palace, they were told to individually state their cases, as they had no collective economic interest. Women were then put on trial as individuals for refusal to pay taxes. Using all means available, the AWU continued its activities and mobilization, with its leaders refusing to pay taxes as well. Ransome-Kuti was imprisoned in 1947 for this very reason, but the movement was not deterred and entered a radical phase, with increasing sit-ins, demonstrations and market closures, including using songs and the ridicule of male power.

A mass demonstration took place on 29 and 30 November 1947 and pulled in more than 10,000 women. The demonstration was repeated ten days later. The alake, in the meantime, employed divisive tactics by promising women positions of responsibility, thus trying to undermine Ransome-Kuti’s influence. In April 1948, Ransome-Kuti again refused to pay her taxes. This time the whole community reacted: on 20 December the men finally broke their silence. They organized a meeting in which they affirmed their desire to support the women in the name of happiness, freedom from oppression and peace in the region. All then settled to wait for the government to give in.

The alake held out until 3 January 1949, when the pressure became too much and he abdicated. The tax on women was abolished (whereas the one on men was increased), and four women, including Ransome-Kuti, were named to a new interim council. It had taken the women nearly three years of continuous struggle to win, during which they had remained cohesive, organized and determined, and had not resorted to violence.

The AWU continued to act as a pressure group every time the interests of Egba women were endangered. In 1952, they took actions against a new water tax (at three shillings per woman per year) to finance a new water supply system. Women had been exempt from water taxation since 1948. While not of the previous scale, demonstrations occurred sporadically until this unpopular tax was repealed in 1960. There were other disturbances in 1952 when the administration tried to bar the women of Abeokuta from holding their now annual demonstration to celebrate the anniversary of the overthrow of Ademola. The police drove them back with tear gas and arrested about 50 women. Ransome-Kuti managed to have the incident discussed by the British parliament.

Strengthened by its accomplishments, the AWU decided to expand into a trans-regional, trans-ethnic structure, and became the Nigerian Women’s Union. Sections were created in many areas, including Kano to the north. Many of its members joined in the struggle for independence with political parties such as the Action Group or the National Council of Nigeria and the Cameroons (NCNC). An executive committee was organized to try to keep educated women and often illiterate businesswomen, including several market representatives, on the same footing. Soon the Nigerian Women’s Union had 20,000 members. These activists were then able to mobilize 80,000 to 100,000 women. The union was more reformist than revolutionary and often drew on arguments deriving from British democracy. It was to later transform into the Federation of Nigerian Women’s Society (FNWS) with the mandate of articulating women’s position in Nigerian society.

Ransome-Kuti’s political activism led to her membership in the NCNC where she was the only woman to hold an executive position. She was also the only woman to join the Nigerian delegation to London in 1947 to lodge a formal protest with the secretary of state for the colonies. During this visit, she informed British unions and the crown of what was happening in Abeokuta. She became a well-known figure to the British press and public, had articles published in the Daily Worker and was even invited by the mayor of Manchester to speak on the condition of women in her country. Increasingly famous for representing women’s interests, Ransome-Kuti was honoured with a doctorate degree, the Order of the Niger, and the Lenin Peace Prize.

If Ransome-Kuti had not been progressive in her views and aspirations, she would have been labelled an ‘objectionist.’ Her dossier is full of objections entered in the interest of the people. Notable among these was her objection to the setting up of the ‘Sole Native Authority’ to the exclusion of the members of the Egba Native Authority.[2] Ransome-Kuti has been described as an ‘eloquent and compelling speaker’ who efficiently used ‘expressive, idiomatic language and very sharp wit.’[3] She also extended support to Mrs. Margaret Ekpo, who had commenced an independent resistance to colonial policies in eastern Nigeria.[4]

In February 1978, Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti was thrown out of a window by Nigerian soldiers ransacking the home of her son, renowned Afrobeat musician and activist, Fela Anikulapo Kuti. She died of her injuries in April that year.

—

Footnotes:

[1] Wayne, TK (2011). Feminist Writings from Ancient Times to the Modern World: A Global Sourcebook and History. California: Greenwood.

[2] Awe, B (1992). Nigerian Women: A Historical Perspective. University of Virginia.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Badmus, I. A. (2006). Political parties and women’s political leadership in Nigeria: the case of the PDP, the ANPP and the AD. Ufahamu. 32(3), 55-91.